Make Popular Sovereignty Great Again

- Republics Don’t Maintain Themselves, It’s Up to Us

by Brian E A “Beam” Maue, PhD

March 2024

By the fall of 1787, Philadelphia was a hot spot for rumors and speculations concerning the Constitutional Convention occurring at Independence Hall. Some city members speculated that the Convention’s delegates might create a more powerful government structure than the nation’s current Articles of Confederation. These members were worried about a more powerful government acting like a new monarchy or dictatorship.

Although the outcome of the Convention was uncertain, it was certain that the Articles of Confederation had proven ineffective for key national-level issues. For example, commerce was inefficient because America lacked a national currency, and negotiations with foreign nations were inconsistent between the states. Additionally, America still had a large Revolutionary War debt but no ability to raise funds with taxation. A stronger government was needed, but how strong would that new government need to be?

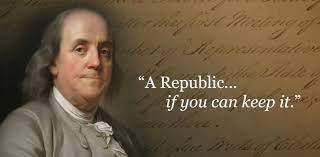

That mystery was solved on the final day of the Convention. A journal entry from Maryland delegate James McHenry recorded what happened on September 17, 1787, as Benjamin Franklin and other delegates were leaving Independence Hall. They were met by a group of citizens, among whom was Elizabeth Powel. She asked Franklin, "Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?"

Franklin replied, “A republic…if you can keep it.”

His response was both a celebration and a warning. The Constitution’s framework of a democratic republic was promising, but it was also an unproven experiment. Previously, rulers had typically claimed the “divine right of kings” or a “heavenly mandate” as the basis for their rule over subjects. Evidence for the supernatural favoritism of these rulers was often linked to the rulers’ prior battle victories.

America’s government would be different. Central to our founding were the concepts of natural rights and social contracts. These ideas had been shaped by great thinkers throughout history, such as Sophocles, Cicero, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke. They had helped form an understanding that individuals are born with rights, including life, liberty, and property. Subsequently, individuals might choose to give away a part of their rights in exchange for a good government’s protection. That exchange of rights-for-protection was evaluated from the individual’s perspective, not the ruler’s, and it could be ended.

America’s Declaration of Independence synthesized these understandings with its claim that “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” This popular sovereignty approach to government can also be seen in our Constitution’s opening words of “We the People of the United States.” These citizen-centric bases for government contrasted sharply with prior political descriptions of countrymen. For example, when the Pilgrims wrote the Mayflower Compact, they referred to themselves as “the loyal Subjects of our dread sovereign Lord King James.”

The Constitution’s self-government approach covered an amount of land that was unprecedented in size, and there was no guarantee that popular sovereignty would last. Indeed, when Franklin had been speaking inside of Independence Hall, he predicted that the Constitution would likely “,,,be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in Despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic Government, being incapable of any other.”

In other words, our American government was based upon individual rights, but if we become lax in our knowledge or activities supporting good government, and if we leave ruling up to an elite few, then a “despotic Government” will be the natural result. Socrates warned us of this possibility over 2,300 years ago within Plato’s Republic. Socrates is attributed to have said, “The price good men pay for the indifference to public affairs is to be ruled by evil men.”

America needs an informed and engaged citizenry who participates in public assembly, debates, and government activities. A great way of understanding the fundamentals of “good government” created by our Constitution is by studying The Federalist Papers. This collection of writings from 1787 and 1788 explores the purpose of the Constitution and the nature of people. These writings have often been cited by Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, and the late Antonin Scalia. If you enjoy video lectures more than reading, then consider viewing Hillsdale College’s free online course The Federalist Papers (please visit online.hillsdale.edu).

Federalist Paper #1 states that it is up to the citizens of the United States “…by their conduct and example, to decide the important question whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.” Active participation, informed debate, and vigilant learning will develop the “reflection and choice” capabilities we need to support “good government.”

May we strengthen our popular sovereignty capabilities in 2024, guard our liberty, and focus our government to become a better government of, by, and for the people.

---

Resources

Franklin’s “If you can keep it:”

https://blogs.loc.gov/manuscripts/2022/01/a-republic-if-you-can-keep-it-elizabeth-willing-powel-benjamin-franklin-and-the-james-mchenry-journal/

The Declaration of Independence:

https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

The Constitution of the United States:

https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript

Franklin’s closing words to the Constitutional Convention:

https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2010/09/17/what-franklin-thought-of-the-constitution/

Socrates warned about indifference:

https://wist.info/plato/3168/

Federalist Paper #1:

https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-1-10

- Republics Don’t Maintain Themselves, It’s Up to Us

by Brian E A “Beam” Maue, PhD

March 2024

By the fall of 1787, Philadelphia was a hot spot for rumors and speculations concerning the Constitutional Convention occurring at Independence Hall. Some city members speculated that the Convention’s delegates might create a more powerful government structure than the nation’s current Articles of Confederation. These members were worried about a more powerful government acting like a new monarchy or dictatorship.

Although the outcome of the Convention was uncertain, it was certain that the Articles of Confederation had proven ineffective for key national-level issues. For example, commerce was inefficient because America lacked a national currency, and negotiations with foreign nations were inconsistent between the states. Additionally, America still had a large Revolutionary War debt but no ability to raise funds with taxation. A stronger government was needed, but how strong would that new government need to be?

That mystery was solved on the final day of the Convention. A journal entry from Maryland delegate James McHenry recorded what happened on September 17, 1787, as Benjamin Franklin and other delegates were leaving Independence Hall. They were met by a group of citizens, among whom was Elizabeth Powel. She asked Franklin, "Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?"

Franklin replied, “A republic…if you can keep it.”

His response was both a celebration and a warning. The Constitution’s framework of a democratic republic was promising, but it was also an unproven experiment. Previously, rulers had typically claimed the “divine right of kings” or a “heavenly mandate” as the basis for their rule over subjects. Evidence for the supernatural favoritism of these rulers was often linked to the rulers’ prior battle victories.

America’s government would be different. Central to our founding were the concepts of natural rights and social contracts. These ideas had been shaped by great thinkers throughout history, such as Sophocles, Cicero, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke. They had helped form an understanding that individuals are born with rights, including life, liberty, and property. Subsequently, individuals might choose to give away a part of their rights in exchange for a good government’s protection. That exchange of rights-for-protection was evaluated from the individual’s perspective, not the ruler’s, and it could be ended.

America’s Declaration of Independence synthesized these understandings with its claim that “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” This popular sovereignty approach to government can also be seen in our Constitution’s opening words of “We the People of the United States.” These citizen-centric bases for government contrasted sharply with prior political descriptions of countrymen. For example, when the Pilgrims wrote the Mayflower Compact, they referred to themselves as “the loyal Subjects of our dread sovereign Lord King James.”

The Constitution’s self-government approach covered an amount of land that was unprecedented in size, and there was no guarantee that popular sovereignty would last. Indeed, when Franklin had been speaking inside of Independence Hall, he predicted that the Constitution would likely “,,,be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in Despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic Government, being incapable of any other.”

In other words, our American government was based upon individual rights, but if we become lax in our knowledge or activities supporting good government, and if we leave ruling up to an elite few, then a “despotic Government” will be the natural result. Socrates warned us of this possibility over 2,300 years ago within Plato’s Republic. Socrates is attributed to have said, “The price good men pay for the indifference to public affairs is to be ruled by evil men.”

America needs an informed and engaged citizenry who participates in public assembly, debates, and government activities. A great way of understanding the fundamentals of “good government” created by our Constitution is by studying The Federalist Papers. This collection of writings from 1787 and 1788 explores the purpose of the Constitution and the nature of people. These writings have often been cited by Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, and the late Antonin Scalia. If you enjoy video lectures more than reading, then consider viewing Hillsdale College’s free online course The Federalist Papers (please visit online.hillsdale.edu).

Federalist Paper #1 states that it is up to the citizens of the United States “…by their conduct and example, to decide the important question whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.” Active participation, informed debate, and vigilant learning will develop the “reflection and choice” capabilities we need to support “good government.”

May we strengthen our popular sovereignty capabilities in 2024, guard our liberty, and focus our government to become a better government of, by, and for the people.

---

Resources

Franklin’s “If you can keep it:”

https://blogs.loc.gov/manuscripts/2022/01/a-republic-if-you-can-keep-it-elizabeth-willing-powel-benjamin-franklin-and-the-james-mchenry-journal/

The Declaration of Independence:

https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

The Constitution of the United States:

https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript

Franklin’s closing words to the Constitutional Convention:

https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2010/09/17/what-franklin-thought-of-the-constitution/

Socrates warned about indifference:

https://wist.info/plato/3168/

Federalist Paper #1:

https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-1-10