Even a Bad Investor Can Beat Social Security

by Knoxville Tea Party

December 2018

We may delve into the history of the present-day trillion-dollar program at some later date, but for now, let's see how well it works.

Synopsis: Social Security is a tax on working people that is sent to Social Security beneficiaries. As soon as revenues are collected, they are spent. Any money left over, after making benefit payments, is loaned to the United States, accounted as a "surplus" collection for that year.

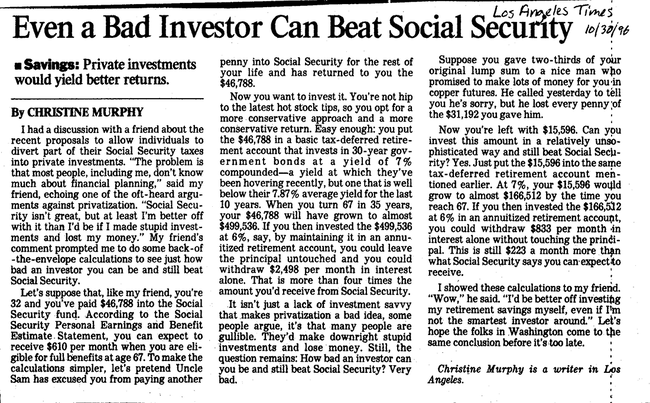

In 1996 the Los Angeles Times ran an article that calculated how much money the author's 32-year-old friend could expect from Social Security upon retirement, and compared that to the amount he could expect if he could have invested all of his money Social Security had taken at that point, right then, into a tax-deferred retirement account without ever paying in another dime.

The upshot was that even if her friend lost two-thirds of his investment to bad decisions and fraudsters, investing the remaining 1/3rd would still allow him to retire substantially better living from his investment interest alone, than the benefit Social Security proposed to take for him from other people's children.

by Knoxville Tea Party

December 2018

- (NOTE: We're not advocating taking anyone's Social Security check here. We're just looking at the mechanics of the program to see how well it serves us. Meanwhile, people have made their plans in good faith based on the federal government's promises, and those promises should be kept.)

We may delve into the history of the present-day trillion-dollar program at some later date, but for now, let's see how well it works.

Synopsis: Social Security is a tax on working people that is sent to Social Security beneficiaries. As soon as revenues are collected, they are spent. Any money left over, after making benefit payments, is loaned to the United States, accounted as a "surplus" collection for that year.

In 1996 the Los Angeles Times ran an article that calculated how much money the author's 32-year-old friend could expect from Social Security upon retirement, and compared that to the amount he could expect if he could have invested all of his money Social Security had taken at that point, right then, into a tax-deferred retirement account without ever paying in another dime.

The upshot was that even if her friend lost two-thirds of his investment to bad decisions and fraudsters, investing the remaining 1/3rd would still allow him to retire substantially better living from his investment interest alone, than the benefit Social Security proposed to take for him from other people's children.

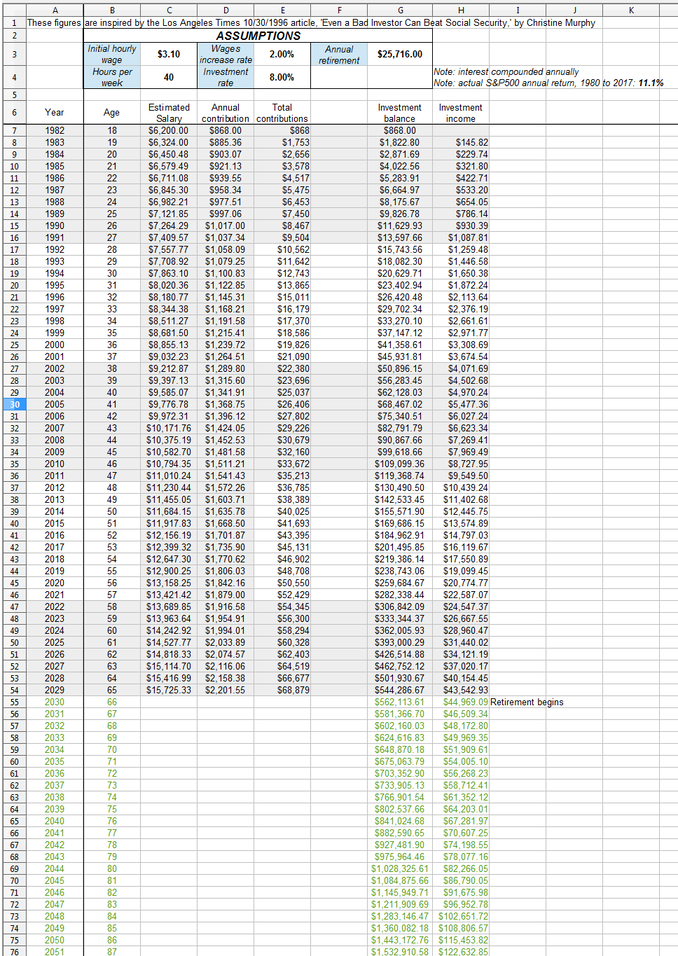

METHOD: We've updated the numbers for the above 22-year-old scenario using the actual Standard & Poors 500 returns from 1996 to 2017, to see how that then-32-year-old worker would have fared. But unlike the original, we assumed that the same gentleman continued his contributions until he retired at age 65. So that no investment wizardry is needed, we've assumed contributions were invested in a tax-deferred retirement fund indexed to the S&P500.

We researched the S&P500 return from 1996 to 2017 (which includes two recessions, the internet bubble, and the housing crisis) and found the total annual return to be 8.2% over those twenty-one years. We then built a simple spreadsheet that compounds the interest and contributions annually (a modest underestimate compared to compounding monthly).

RESULTS: If he continued to invest the same portion of his salary that Social Security normally claims, at age 65 our gentleman's retirement fund would contain $2,057,160 that he could leave to his children or family, and provide an average annual investment income of $168,687.

For comparison, we entered this gentleman's information from our spreadsheet into Social Security's benefits calculator. Social Security's online benefits calculator indicates that Social Security would offer the same gentleman $25,692 in annual retirement benefits, a considerable downgrade.

_______

But now, dear Readers, we get to the meat of it. Critics and naysayers presented with the previous information have objected "But what about poor people, who can't save?" What if there's a crash? Or returns fall short? So, we've computed the same amounts and figures for someone who earns the federal minimum wage. (That's right, federal minimum wage.)

METHOD: We demoted the original article's worker, stopped him from attending college, and had the same gentleman start at minimum wage at age eighteen in 1982, working just forty-hours a week (your humble author held two full-time minimum wage jobs at that same age without difficulty or distress), and we have him staying at that minimum-wage level, adjusted to roughly match the federal increases, until retirement at age 65. In fact our schedule has him only earning $6.32/hr in 2018, when the actual federal minimum wage is $7.25.

Using the same reference (S&P500 return), we find the S&P 500 has returned 43.919-fold over the thirty-five years from 1982 to 2017, or an annualized return of 11.4%. We knocked 3.4% off that, and assumed our gentleman only got 8%.

RESULTS: Putting the same amounts Social Security takes from his employer and deducts from his check, and investing them in any ordinary dirt-cheap S&P 500-indexed retirement fund--no investment savvy required--leaves our minimum-wage worker with an annual investment income of over $44,000 dollars, and also a whopping $562,000 dollar investment account he can leave to his children.

And of course nothing stops the gentleman from working an extra ten hours a week, or otherwise saving more of his wages for retirement, leaving him even better off.

CONCLUSION: Even a minimum-wage worker can beat our trillion-dollar-a-year Social Security program, and beat it very handily.

We researched the S&P500 return from 1996 to 2017 (which includes two recessions, the internet bubble, and the housing crisis) and found the total annual return to be 8.2% over those twenty-one years. We then built a simple spreadsheet that compounds the interest and contributions annually (a modest underestimate compared to compounding monthly).

RESULTS: If he continued to invest the same portion of his salary that Social Security normally claims, at age 65 our gentleman's retirement fund would contain $2,057,160 that he could leave to his children or family, and provide an average annual investment income of $168,687.

For comparison, we entered this gentleman's information from our spreadsheet into Social Security's benefits calculator. Social Security's online benefits calculator indicates that Social Security would offer the same gentleman $25,692 in annual retirement benefits, a considerable downgrade.

_______

But now, dear Readers, we get to the meat of it. Critics and naysayers presented with the previous information have objected "But what about poor people, who can't save?" What if there's a crash? Or returns fall short? So, we've computed the same amounts and figures for someone who earns the federal minimum wage. (That's right, federal minimum wage.)

METHOD: We demoted the original article's worker, stopped him from attending college, and had the same gentleman start at minimum wage at age eighteen in 1982, working just forty-hours a week (your humble author held two full-time minimum wage jobs at that same age without difficulty or distress), and we have him staying at that minimum-wage level, adjusted to roughly match the federal increases, until retirement at age 65. In fact our schedule has him only earning $6.32/hr in 2018, when the actual federal minimum wage is $7.25.

Using the same reference (S&P500 return), we find the S&P 500 has returned 43.919-fold over the thirty-five years from 1982 to 2017, or an annualized return of 11.4%. We knocked 3.4% off that, and assumed our gentleman only got 8%.

RESULTS: Putting the same amounts Social Security takes from his employer and deducts from his check, and investing them in any ordinary dirt-cheap S&P 500-indexed retirement fund--no investment savvy required--leaves our minimum-wage worker with an annual investment income of over $44,000 dollars, and also a whopping $562,000 dollar investment account he can leave to his children.

And of course nothing stops the gentleman from working an extra ten hours a week, or otherwise saving more of his wages for retirement, leaving him even better off.

CONCLUSION: Even a minimum-wage worker can beat our trillion-dollar-a-year Social Security program, and beat it very handily.